The Queer Chronicles

Belén Maya in her latest production “Yo Quiero Ser Humano”.

The following is a transcript of a talk I presented at Stonewall, Oxford St Sydney on Wednesday 22nd February at 5.30pm. The presentation was curated by Annalouise Paul Dance Theatre for Pride Amplified – an offshoot series of events aligned with World Pride 2023.

This topic of discussion examined the position of ‘difference’ in flamenco and looked at the invisibility and presence of homosexuality and gender conformity in flamenco. I was curious to examine how historically this voice has been managed as a consequence of the conventional image flamenco portrays. In an optimistic world what can be gained by placing the ‘queer gaze’ in the spotlight.

Welcome!

I’d like to acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land on which we meet today, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation and pay my respects to Elders past and present.

I’d also like to thank Annalouise Paul for coordinating and helping to bring together our guest speakers this evening, together with my hosts in Sydney Philippa Damascus, Paul and Sue Tracey for their kindness and generosity.

My name is Tomas Arroquero. I am originally from Melbourne in Australia. I am a flamenco dance, spending over 20 years working as a dancer in Spain, the source of flamenco. Since returning to Australia in 2011 I have undertaken 3-postgraduate studies, which include a 2-year research Masters at the VCA, University of Melbourne. My masters focused on the presence and transformation of traditional form within contemporary performance settings.

As a young man I did struggle with my sexuality. From the outside I willingly went through life’s institutions complying with all that was necessary to prepare myself to be a quasi-Australian in the guise of a heterosexual man.

As a first generation Australian to Spanish immigrants I already felt different.

However I carried with me this sense of guilt and shame because I could never quite live up to being the person that I could see reflected in the world around me.

Subconsciously I sought out a space where I could express myself and embrace these disquiet thoughts and fears, and turn a negative into a positive.

Dancing flamenco helped me achieve this, although I didn’t really understand it at the time. All I knew was how much I enjoyed dancing. I had a flair for it and the rest is history.

I wanted to share with you a little of myself to help both begin and also open up the conversation today about the invisibility and presence of homosexuality and gender conformity in flamenco.

I am very excited to present some pre-recorded excerpts from 2-interviews, which were set up through Annalouise and me. Both of us felt the need to include a contribution on this topic from others outside Australia and particularly a voice from Spain as the cradle of flamenco.

The two artists who generously come along for the conversation are Ryan Rockmore from the US and Belen Maya from Spain.

Ryan is a queer flamenco dancer-researcher, an educator and independent school administrator. His creative and academic work focuses on the presence of the body in space, the study and writing of flamenco history, and the anti-behavioural practice, which include racial and discrimination within the tradition of flamenco.

Belen Maya is a regarded as a principal figure in flamenco. She is a dancer, choreographer and educator. She is the daughter of Mario Maya, a Romani man considered one of the most innovative flamenco dancers in Spanish history and Carmen Mora, also a flamenco dancer.

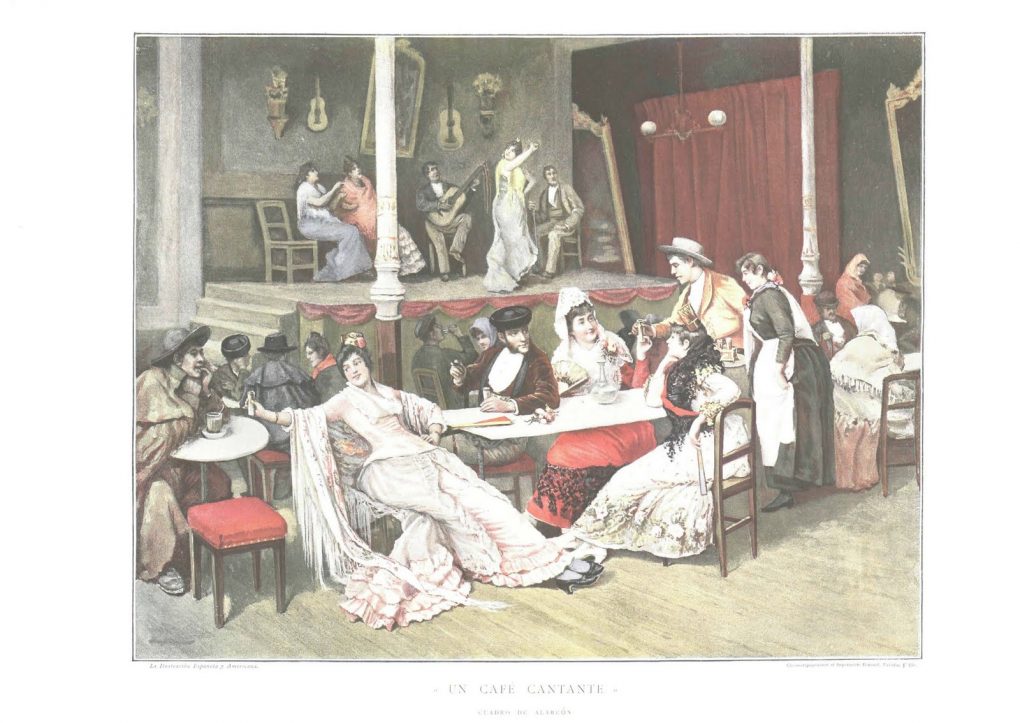

Flamenco as a tradition is specific to Andalucian culture. It has made its own transitory journey from the adaptation of flamenco as a practice exclusively within a racial minority, through to its inaugural appearance as a public spectacle. This culminated in the last nineteenth century in public venues referred to as the Café Cantante period in Spain and has since been re-enacted in theatres, which has gathered momentum and is now recognised globally as a by-product of Spain.

Flamenco’s evolution as an art form has always been apparent. Yet as a dance practitioner I am constantly confronted with a dilemma of making binary choices between what is categorised as traditional flamenco, and by this I refer to the descriptive elements, which include gender, to those choices I make as a queer person prescribing to a normative form of behaviour, defined within the tradition itself.

First of all let’s focus on the term queer and try to imagine what queering in flamenco looks like? If we were to re-position the queer aspect to the dominant centre then how can queering in flamenco make us rethink the traditional narrative?

Guitar and Women

Gitana y torero con el Guadalquivir al fondo de Gonzalo Bilbao. Museo Bellver, Sevilla. Circa 1920

Since the end of the 19th century, the flamenco guitar or toque presented its own peculiarities, with the absence of women as instrumentalists in flamenco. Traditionally, in Andalucía, and more specifically in a place like Jerez de la Frontera, some parents accompany their little girls to dance classes, while the boys attend flamenco guitar lessons. Despite the low ratio of boys to girls who learn flamenco dance, the presence of girls learning how to play the flamenco guitar is practically nil. While a number of children fall away before reaching adulthood, those who persist in flamenco maintain gender roles, which parallel childhood experiences.

Notwithstanding rapid changes in technology, the principal mindset of both mental and physical desire between the sexes has generally remained unchanged.

In flamenco style tablaos (cabaret restaurants) performance sensibilities are primarily categorised by gender. Women commonly interpret forms of dance while guitarists are usually always men. In a commercial setting, the gender/sexual dynamic played out at once imbues and energises the performance. Stereotypical images of flamenco portray the form and its practitioners as passionate, fiery and seductive. Descriptions are often anecdotal about love, sex and the allure or rejection of men and women strong in character to each other.

The dominant Western canon of dance continues to be highly valued in the west. Stories, now classics, continue to be upheld and endure the test of time. Many of these narratives have been shaped through a romantic lens. Genres such as ballet, opera and musical theatre, codify and more often limit gender roles in performance. This is not exclusive to traditional forms of expression. Pina Bausch’s modern dance company has also been criticised in its rendering of gender politics. Despite producing groundbreaking work that pushed dance theatre through territory previously unexplored, much of the work still sits within traditional concepts of gender.

Is this because we predominately construct ourselves through the looking glass of others? This statement presumes that as individuals the notion of constructs, which have manifested their way over centuries into ordinary life, limit and/or control how we look, think and feel to varying degrees. In view of this have we actually moved on at all since the representation of gender in art from the ancient world until now?

In flamenco, despite the continued presence of men playing the guitar, there is evidence that suggests the contrary. During the latter part of the 19th century, Café Cantantes (a.1847 – 1920) appeared as popular establisments throughout several parts of Andalucía. These singing cafes echoed both the demand for cante (flamenco song), and made the dance aspect of flamenco appear as the focal point in perfomance. After a period of restricted viewing, both cante and baile (flamenco dance) resonated with a larger and more discerning public.

Historical records mention several women as great exponents of dance and song but also formidable interpreters of the guitar. Such artists include Dolores la de la Huerta, la Antequerana, la Serneta and la Cuenca. In the 20th century others aspired to a similar vocation like Anilla la de Ronda, Tia Marina Habichuela, Adela Cubas and Victoria de Miguel.

Yet historical and cultural issues have separated the flamenco guitar from the hands of women. As reiterated, social learning environments for the flamenco guitar are predominately male. The symbolic image of the guitar as external to the body is commonly referred to as an instrument of power. This analogy between image and power is often linked to its feminine form – the curvature of the guitar commonly referred to as the hips of a woman’s body. When a guitar is used to create music, subconscious sexual and romantic notions are at work. Historical transcripts and film reinforce this notion, which continues even today as a significant or recurrent theme. For example, a relatively recent Woody Allen film that comes to mind is “Vicky Cristina Barcelona” (2008), where the mise-en-scène includes several moments of energetic guitar playing, which speaks volumes and sets numerous scenes. The sound of the flamenco guitar immediately transports us to Spain. Its emotional resonance conjures up those images so transcendent with flamenco, like the bull, the sun, the orange trees and the almighty colour red.

Associations between form and gender placement in flamenco have also been reinforced in 19th century paintings. Referred to as La Edad de Oro del flamenco (The Golden Age of Flamenco), renowned painters such as Federico Godoy Castro (1869 – 1937), Carlos Verger Fioretti (1872 – 1929), Julio Romero De Torres (1874 – 1930), Joaquín Sorolla (1863 – 1923) and Gonzalo Bilbao (1860 – 1938) crystallised a set of aesthetics, which underline the outward form of flamenco even today.

Men more often painted and produced works that became significant, making them also responsible for both the guardianship and the distribution of their paintings. Across the board, the dominant presence of men in public and management positions, often deemed inappropriate for women, slowed down female equivalents. Even today, male guitarists are more directly involved in the tasks of composition, record production and arrangement, compared to women.

A journal article titled “La Madrugá” published by the University of Murcia (2015), catalogues a list of flamenco festivals throughout Spain in 2014. Numerous categories note the ratio of male to female participants, across performance and production. It found that 8 out of 10 participants performing flamenco were male. The toque (guitar) represents almost a third of performers, along with 41 percent of cante (song) and 28 percent dance. Yet compared to 47 performances by female-cantaoras (singers), those by male-cantaores (singers) were more than double at 103.

Jesús Carmona, dancing with (from left) Victor Marquez, Paco Vega, Daniel Jurado, Photo Credit: Hiroyuki Ito for The New York Times

While the number of male flamenco dancers has increased, they still make up slightly fewer than their female counterparts (49 to 52 percent respectively). However female exclusion in both toque (guitar) and percussion has not varied at all over the last two centuries. With respect to “other instruments” during the 2014 Flamenco Biennial (Seville), only 3 women collaborated in shows compared with 43 men. By comparison background accompaniment in the role of palmeros (hand clappers), jaleos (flamenco chorus) and compás (rhythm) was more favorable to women, but their presence is still somewhat less than a third of their male counterparts. Further to this analysis, only 16 percent of women participated in technical aspects of production, which included specialist tasks in scenography, lighting, sound and audiovisual management. In directing and coordinating events and activities, men double in proportion to women, while production and communication tasks include a greater presence of women (43 percent compared to 14 percent for men).

On reflection, the representation of gender in flamenco has been encapsulated in the art world during the 19th and 20th centuries. Understanding that most contemporary societies have been structured through patriarchal systems, which continue to be dominated by men, it is easy to comprehend how structures of power defend and disseminate the roles of women in society to varying degrees. This representation of gender in art and flamenco played an important role in the construction of the idea of Spanish dance, which has become the country’s unifying symbol and one of Spain’s greatest exports.

By Tomas Arroquero | 5th January 2021

Trans

form

ation

This year marked the 24th Festival de Jerez with the critics’ choice award going to Manuel Liñán’s production of “¡VIVA!” I have not seen this work live but have been fortunate to see two productions by Manuel Liñán; “Sinergia” and “Baile de Autor” respectively. After watching several excerpts and reading a number of online press reviews, which praise “¡VIVA!” as a triumph, Liñán manages to glean ideas from a selection of previous works while exploring personal elements that continue to resonate most importantly in him.

At the heart of the work is an ongoing discourse that many flamenco artists continue to grapple with and try to overcome. This concerns the evolution of flamenco as a tradition, while it tries to incorporate more universal values in theatrical performance settings. For at least the last two decades many artists have explored flamenco through the lens of contemporary form.

Liñán is first and foremost a flamenco artist, skilled in the dance aspect of the form, and a body steeped in the principles of flamenco. Like him, many of his contemporaries generate work from a range of disparate sources. Some use more folk and popular forms while others have gone in search of the experimental spirit of the modernist vanguard. To some extent it’s now become fashionable to bend the rules but, generally, most productions still rely extensively on a flamenco mandate, re-contextualising the art form within the margins of tradition.

In my view Liñán sits more at the conservative end, making work accessible to audiences by satisfying preconceived notions of what flamenco represents. As such, the prize-winning accolade does not rest on its groundbreaking choreographic standing or conceptual achievement. Instead it capitalises on a knowledge both culturally and socially embedded, which makes it connect more readily to audiences and especially those discerning critics in Spain.

As a long-standing tradition, the resonance of flamenco reigns supreme in a place like Jerez de la Frontera, defining many aspects of everyday life. Officially named Cuidad de Flamenco (City of Flamenco), Jerez inaugurated its first official festival dedicated to the art form in 1997. As a festival it brings together amateur and professional, enthusiasts and aficionados from local, national and international spheres.

In this particular performance, a group of men pose as women in gaudy flamenco attire and vestiges of sympathy expressing a more explicit form of flamenco. Simultaneously however, they are driven by the charged, high-definition of opposition, masculine/feminine, liberation/repression, imitation/genuine, complex/straightforward, where beneath the surface of one side of a duality flows the undercurrent of its opposite.

Liñán demonstrates skill dancing in both male and female attire, which he has expertly crafted. His ensemble of men has also established careers in the art form and no doubt delivers a high level of technical skill and artistry, each of their own accord and to varying degrees. The dancers are characterised as divas; a flamenco, drag cabaret, which both ridicules and uses humour to trivialise the art form, much in the same way that transvestism does. It is precisely this aspect of the performance where the audience connects. The ostentatious nature of their costumes, make-up and hair are not that dissimilar from the truth. The way they move, behave and carry themselves as men also matches their female counterparts, using a palette of prescribed movement and gesture both personal and exaggerated in its staging.

In a press conference prior to the performance, Liñán defends the work as a gender transformation rather than a representation of women, where each member brings their own set of skills and identity, visualising their feminine side through both costume and dance. On the one hand the drag metaphor appears as a sign of liberation – a border crossing that signifies agency and newly constructed identities. On the other hand we see a mere masquerade that hides the performers’ underlying identity. Only in the final scene is the role-play reversed with each performer removing their costume, shoes and wig to reveal the ramifications of a more vulnerable self, sprinkled with just a few scattered remains. However, for the courage to be believable and not laughable, the palpability of the loss or the vulnerability must be felt and exhibited equally. The loss has to somehow trickily walk alongside the courage in every moment and this, I suspect, is difficult to achieve. In contrast, Liñán uses transvestism to describe two contradictory but inseparable performances. The first calls attention to itself as performance, while the second attempts to eliminate any trace of performance and pass unnoticed as the opposite sex.

It is interesting for me as a gay man, to witness the progression, or rather the lack of response to the obvious metaphor being played out here. Yet it would be reductive to suggest that all men who dress in drag are homosexual, or that homosexuality immediately implies drag. Many transvestites are heterosexual, or bisexual, and therefore no clear relationship can be established between drag and homosexuality. Nevertheless, the two are often interlinked, as drag has played a fundamental role in gay liberation movements all over the world.

Dancers: Manuel Liñán, Manuel Betanzos, Jonatán Miro, Hugo López, Miguel Angel Heredia, Víctor Martin, and Daniel Ramos.

During Spain’s economic liberation in the ’60s and early ’70s, official pro-regime film participated as a propaganda machine for tourism, propagating the notion of rapid modernisation. Strategically combining culture and tourism under one banner, the Ministry of Tourism circulated picture postcard images of flamenco stereotypes conceived for an expendable market. Carefully constructed, flamenco dancers dressed in colourful costumes adorned with polka dots, flowers, ruffles, fans and shawls, exuded an aura of exoticism. Liñán’s work cleverly references these rhetorical, overblown images in the form of dancing drag personas, epitomised through an unrestrained passion and spirit, bursting forth into flamenco because it cannot be contained inside any longer. Simultaneously, transvestism is a particularly apt metaphor to describe post-Franco Spain on account of the fact that the Transition appeared to be accompanied by the first public manifestations of drag. The rapid increase of drag cabarets and the first gay manifestation, headed by Catalan drag queens in the ’70s, signalled a sexual transition that paralleled the political shift to democracy. While drag cabarets and transvestism certainly existed prior to the fall of Franco’s regime, the Transition permitted a formerly denied visibility, and heightened public awareness.

Curiously drag culture has manifested its way into Spain’s daily life. For example in Andalusia, ‘Carnival’ festivities in both Cadiz and Tenerife incorporate an annual drag pageant embraced and supported by a discerning local public. Men predominately compete in a walk down the runway for the best costume display. More recently and comparably RuPaul’s Drag Race has also propelled drag culture into the mainstream. Yet drag cannot transcend the gender norms that it invariably inscribes, and nor is it a new identity. Drag has a long history of destabilising identity and rendering it unresolved.

As in previous works by Liñán, references to his sexuality are both apparent but also somewhat disguised within the principles and aesthetics of the form. For example, in “Baile de Autor” there is a segment where Liñán chooses to dance in a white bata de cola (trail dress), using both a fan and shawl, with extraordinary execution and skill. Yet beyond the first few minutes the gender difference vanishes. I was no longer watching a man in a dress but rather a person transcending the fine details of a form and expressing a genuine self because that is the way he feels it.

Other male dancers, including some prominent figures in flamenco such as Joaquin Cortéz, Marco Flores and David Romero, have also worn tail dresses and managed it with equal precision. However the use of such objects traditionally associated with women and regardless of gender, tend to end up being used in exactly the same way.

The cultural transvestism in Liñán’s piece reflects his personal agenda and offers both a celebratory and clever approach to reframe a new work. Together with his ensemble, Liñán symbolises a liberatory desire, which fleshes out both the context of gender, while simultaneously echoing the political landscape of change in Spain. Conversely, the modelling of drag as performance and within its boundaries, exaggerates heterosexual gender norms, which both oppose and comply with the regimes of power that constitute him/her as a subject. In order to exist within a socio-political system, the drag performer is forced into complicity, implying that beneath the façade little has changed. Despite this contextual limitation, Liñán defends and seeks cross-dressing as a form of expression beyond its derogatory or comic sense. The ambiguous nature of drag is also the source of the work’s theoretical and cultural interest. Drag has found voice as both an underground subculture and more so now in mainstream society, symbolising a freedom of expression, ruled out during 40 years of cultural oppression in Spain. The long-term effects of this regime have unquestionably left lasting impressions on the Spanish political, cultural, and social scene. Flamenco became and continues to be a recognisable symbol served up to the tourist in the form of a product and a brand of national marketing, reinforced through historical transcripts and film.

In an attempt to transcend the drag façade “¡VIVA!” requires each daner to interrogate their practice in order to create an alter-flamenco drag performer. While this is not a new persona in itself, there is a tension as each artist reaches in and tries to grapple with his or her own personal demons. Experiences of rejection, difference or marginalization, which have arisen through heteronormative codes in mainstream society, act as a primary vehicle.

There is always a sense that Liñán tries to replicate these experiences in his work, leaving us with an honest interpretation of his life or others coming full circle. Seeing him dance brings to my mind an eccentric child back in the early ’90s who couldn’t articulate why he felt socially awkward. A child who sat alone or sometimes felt like a wallflower but came alive dancing and twirling in a pretty, colourful dress. A child, who lost himself in a dance and managed to discover a kaleidoscope of colour, mixed with feelings of freedom and a higher self. Untouchable. Full. Absorbed in the moment, free from inhibition. A child who dances to express and now wants to work.

By Tomas Arroquero | 16th April 2020

Flamenco Files

When it comes to flamenco and the evolution of an art form, almost all historians describe accounts as approximations because so little of its history has been written. These uncertainties are kept alive as stories, but the storytellers often contradict one another or take on the character of the author who sometimes imbues the story with their own bias. For example, if a reporter interviews a flamenco from Córdoba, the interviewee will almost definitely claim that Córdoba is the “cradle of flamenco.” However, the interviewer is likely to receive the same information from a flamenco in Jerez de la Frontera, Seville or Granada, because each of these places has been instrumental in the development of flamenco at different times.

Regional pride pervades amongst flamenco artists from different regions in Andalucía. Regionalism is also reflected in the many different song forms or palos, and these are grouped into different song families. Some families are classified through measured rhythmic cycles, which act as a marker for identification. For example, tangos in 4/4 time is both a palo and a song family, which includes the palos of tientos, tangos and tanguillos.

Different styles have also developed within certain song forms, and this has contributed to the convoluted classification of styles. For example, most flamenco historians will connect the song form of soleá to Cadíz or Seville, but there are several soleares specific to precincts in Seville like soleá de Triana, or different cities in Spain such as soleá de Alcalá, de Jeréz, de Cadíz, de Lebrija and Utrera. Consequently there are hundreds of song styles in flamenco because adaptations have developed over time amongst specific communities and were popularised by key individuals.

As flamenco dancers, we concern ourselves firstly with form and the practice of repeating measured sequences with musical accompaniment. Only through experience do we encounter stories about different song forms, which furthers our knowledge and deepens our relationship to the art form.

By Tomas Arroquero | 5th January 2020

Flamenco Women

An unexpected film documents an ensemble of female flamenco dancers during a six-day rehearsal process in 1997. The film titled “Flamenco Women” culminates in a dramatically staged event, which takes place in a large, private drawing room before a swarm of celebrities.

From the director and musician Mike Figgis, the film is captured in both a showing room and the famous Amor De Dios studios in Madrid. The dance protagonists, Eva La Yerbabuena and Sara Baras, are pioneering artists of their generation and practice flamenco in a way that has now become standard for female performers in the 21st century.

Footwork plays a much more significant role in their work compared to the work of women of former generations. Still maintaining the traditional feminine role, these women compose their solos much the same way as jazz musicians do, referring back to the rhythmic meter underpinning the structure of the dance.

Figgis captures a moment in flamenco’s history and manages to convey a key quality through its poetry and imagery. Like a fly-on-the-wall documentary, the film records realistically the labour of the rehearsal process. Both Yerbabuena and Baras grapple to convey their intentions to musicians and other dancers steeped in the same discipline. Beyond translation these ideas alter the relationship between steps and their traditional arrangements.

The space these artists create while still maintaining orthodox forms of behavior – as flamencos and as women in flamenco – empowers the next generation to take more risks.

Watch the film here:

By Tomas Arroquero | 5th January 2020